Pleasant Grove and its Inhabitants

The House that Mary Cummings Built

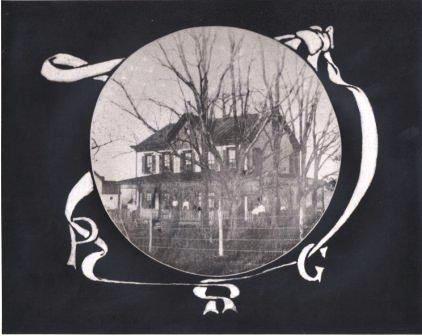

After Mary Cummings’ husband, James Cummings, died in the 1880s, she sold twenty acres of the 50 acre farm, and with the proceeds built a new house, completed in 1893. Her grandson Andrew J. Cummings, Jr., told the story in his CCHS oral history interview:

"She sold twenty acres of land for $2,500, which is now Rollingwood. She built that house; that house only costs $2,500, but it’s a beautiful old house."

Pleasant Grove was named for the many trees surrounding it, especially the very large white oak tree next to the house. In some documents, the house and farm are referred to as Oak Grove. Andrew Jr. claimed the beautiful tree was larger than the famous Wye Oak on the Eastern Shore. It was struck by lightning in the 1960s, and had to be cut down, but that was after the Cummings family had moved from the house. He also described the other trees around the house, shown in a family photograph:

"This was a very large beech tree, and the big oak tree, and these are walnut trees…. When they subdivided the place, they put a road right down through there, and they tore the beech tree out and ran the road right alongside the big oak tree."

Andrew J. Cummings, Jr., who was born in the house on December 6, 1915, three years after his grandmother Mary Cummings died, remembered it well:

Yes, a very nice porch. We used to have rocking chairs out on our front porch; we would sit there and rock. Around the side, we had it screened in, and my father had a little cot around there where he could take a rest.

Andrew Jr. lived at Pleasant Grove with his father, mother, and his maiden aunts. In his CCHS oral history, he described the house in more detail, beginning with the bedrooms on the second floor:

There were four large bedrooms in the house. After my Aunt Cecilia died [in 1913], my Aunt Alice and Aunt Agnes shared one room, and my mother and father shared the other, and I had the third room. And the fourth room was a spare room, for guests. The house had two nice parlors. In the old days, they had a front parlor and a back parlor. We had a dining room and a large kitchen. Almost all the entertainment went on in the dining room. If you were a special guest, you got into the parlor!

Today, the front and back parlors are one large room. On the attic floor, there were two additional rooms under the gabled roof. Andrew Jr. remembered hearing the rain in the attic bedrooms as it fell on the tin roof above.

The house was heated by coal burning Latrobe stoves that were inserted in the cast iron fireplaces. Although the Latrobe stoves have been removed, the original marble surrounds remain. The stoves kept the whole house warm, with the exception of Andrew Jr.’s bedroom, which was located above the kitchen:

Each of the rooms in the house had a fireplace, except the kitchen, and a round cast iron stove sat in the fireplace. It burned coal, anthracite coal, hard coal…. They would keep the room nice and warm. A lot of heat went up the chimney.... We had a ventilator in each upstairs room that was adjustable. A blast of heat would come out of it and keep the upstairs rooms nice and warm. Except my room. My room was over the kitchen stove, and the kitchen stove would go out at night! Fortunately, my aunt [Alice] would get up early and build the fire in the kitchen stove.

The bathroom upstairs, of course, being the highest part of the system, was the first to run out of water. Somebody would go in the bathroom, they’d go to wash their hands, and there wouldn’t be any water. They’d yell down, “Turn the water on!” Somebody would have to go out and turn the pump on. Night or day, cold or rain, somebody would have to go out and turn the switch on.