...Work that has been both a Profit and a Pleasure...

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, many middle-class women in cities and towns across the United States created and joined clubs. Some of these clubs were purely social, while others focused on education, culture, and social reform. These were acceptable ways for women to participate in public life in this period, and while middle-class women had more opportunities to develop women’s associations, women of all backgrounds, regardless of race, class or region were involved in this movement in the Progressive Era. Women’s clubs were a central force in the establishment of public libraries, and the leadership of women in the formation Chevy Chase Free Library Association is an excellent example. But in addition to advocating for libraries, literary clubs for women were particularly popular, especially for college educated women and those who hungered for more education. These clubs offered the opportunity for intellectual engagement and self-development in a period when women could not vote and few middle-class women were in the paid workforce.

In the fall of 1899, four residents of the new suburb of Chevy Chase, Elizabeth Verrill, Mary Robertson, Fanny Richards, and Grace Bowen, met to form their own literary club for women. They called their club the “Chevy Chase Reading Class.” They were inspired by a neighbor, who told them about a similar group, and their name describes their intentions for the group. They would develop annual programs that provided members the opportunity to lead discussions on a variety of texts. This was “serious work,” and hence the word “class” in the name of their group. They developed a plan for meeting once a week from October through April, and by the second year, they expanded the group by inviting four other Chevy Chase women to join them.

Founding member Mary Robertson was still attending meetings in 1962.

The Chevy Chase Reading Class, like the Free Library Association and the Literary Club, was an early organization that helped residents of the new community build social ties. General descriptions of the Reading Class Members are below, but feel free to jump ahead to the short biographies of the founders and early members, as well as the lists of texts that they read between 1899 and 1931. Although we know that the Reading Class met long after 1931, these are the years for which we have records.

Reading Class Members: read biographical sketches of the founders and early members.

Reading Class Book Lists: read transcriptions of “The Outline History of the Chevy Chase Reading Class” (1899-1925) and nine annual reading programs (1919-1931).

Common Characteristics Shared by Reading Class Members

The founders of the Reading Class shared many characteristics. They lived within walking distance of each other. They were among the first residents of the new suburb. They were well-educated – at least two were college graduates. Two worked as teachers before their marriage, and one held a civil service position in the Department of Commerce and Labor. All four of the founders were married, and their husbands worked in the newly expanding federal government bureaus and departments. Their homes were on the side streets of Chevy Chase, in contrast to the grander homes on Connecticut Avenue. They all had young children, but their households were likely prosperous enough for them to have domestic help. Three were members of the same church. They were advocates for woman’s suffrage, and many were active members of other voluntary organizations.

The most important characteristic, however, was their shared desire to read and learn, to be challenged as well as delighted by literary scholarship. In 1914, at the time of the death of one of the founders, Elizabeth Verrill, the members described both her leadership and their participation in the Reading Class as“...work that has been both a profit and a pleasure.”

Where they lived

These maps of Chevy Chase, Section 2, show where the first four members lived and where the larger group of members in the 1905 photograph lived.

The homes of the founding members of the Reading Class, shown on a 1909 Plat Map of Section 2, Chevy Chase. The locations of the homes of the members shown in the group photograph taken in 1905. We do not have street addresses for three members.

Membership Rules

As we show in the Reading Class Book List page of this exhibit, by the 1920s the members of the Reading Class prepared small annual program which listed the meeting date, topic and leader for each meeting. At the end of each program, the members included seven rules for the group.

In Rule No. 1, membership was limited to 20 and only to residents of Chevy Chase. They seem to have determined that 20 was about the right size for the group to do its work efficiently. But they also restricted membership geographically. Rule No. 7 describes how this process worked. If “Chevy Chase” could refer to “any outlying district of that name,” then members who lived in Martin’s Additions to Chevy Chase would be eligible to join the group. However, perhaps in deference to the founding members, all meetings were held in Section 2.

Schools for Young Children

There were no day care centers for young children, but there was a kindergarten -- Klein's Bakery School Kindergarten, and a number of the Reading Class members sent their children to it. We don’t know the hours of its operation, but perhaps it coincided with their weekly meetings.

Child Care and Domestic Servants

If their children were not at kindergarten, who took care of them while their mothers were at their 90 minute meetings each week? According to the 1900 and 1910 census, only five of the Reading Class households had “live-in” domestic servants. But it is likely that other households hired domestic servants who “lived out.” These workers lived in their own homes, in Maryland or in the District of Columbia, and walked or traveled on the streetcars to Chevy Chase for daily work. Although we don’t have specific evidence for those workers who lived out, based on historical accounts of domestic workers in the District of Columbia, the majority were likely women of color.

Alice Claytor, shown here with Helen Tucker’s daughter Jean in the middle photograph, lived with and worked for the Tuckers for at least 10 years as nurse and a maid. The Tuckers also had a live-in cook. Helen Tucker’s husband Charles took many photographs of their family. These photographs suggest that Helen enjoyed being with her children, but her husband also photographed her reading.

Alice Claytor with Jean Taylor Tucker, c. 1902.

Helen Zimmerman Tucker, reading in her home on East Lenox Street.

Woman’s Suffrage

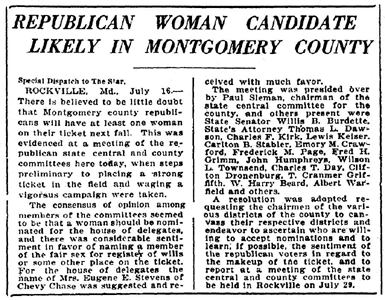

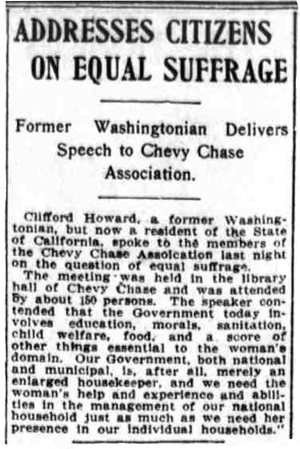

By 1905, several women in the Reading Class were involved in the movement for woman’s suffrage. Two women, Gertrude Stevens and Hattie Howard, were joined in this activism for voting rights by their husbands. Hattie Howard and her husband Clifford Howard, a lawyer and writer, were strong advocates for woman’s suffrage. Clifford was a well-known supporter of the vote for DC residents, for both men and women.

Gertrude and Eugene Stevens supported suffrage for the residents of Washington before they moved to DC, again, for both men and women. Gertrude, a graduate of Mount Holyoke, was a member of the Maryland State Equal Suffrage League. With other suffragists, she lobbied President Wilson in 1915. After the Nineteenth Amendment granting women the vote was ratified, she was chosen as a delegate to the Maryland Republican convention, and she ran for elective office in 1926. She did not win, but she remained involved in county and state politics for the rest of her life.

Voluntary Organizations

Many members of the Reading Class were involved in voluntary organizations. Several worked for organizations that focused on the needs of children and mothers. Here are just two examples:

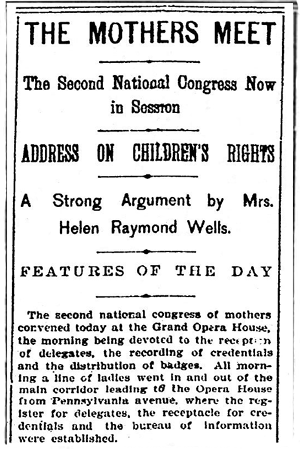

The Mother’s Congress was not so much a charitable organization as it was an advocacy group. It was founded by Chevy Chase resident Mrs. T. W. Birney who lived on West Kirke Street. A former journalist and writer, she worked with philanthropist Phoebe Hearst to bring experts and interested members of the pubic together to discuss the pressing needs of mothers and children. Both Elizabeth Verrill and Grace Bowen attended these multi-day conventions. One of the outcomes of these large meetings was the creation of the organization that is today the Parent Teachers Association.

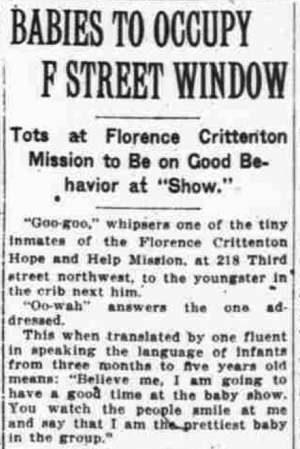

The Florence Crittenton Mission was a national organization that helped support local homes for unwed mothers. Their fund-raising structure involved the creation of local “circles,” what we might call a grass-roots strategy today. Many women in Chevy Chase participated in these circles, raising money for the Crittenton Home in the District of Columbia which sheltered single mothers and their infants. Mary Robertson was the President of the Lady Managers of the Crittenton Home in DC, serving in this role during two different periods, 1916-1921 and 1923-1933. She was also a recognized leader at the national level of the Crittenton Mission.

Both the Mother’s Congress and the Crittenton Home and Circles are examples of the remarkable achievements of many women even as they stayed within the prescribed gender roles for women of their background and class status. During the Progressive Era, it was thought that women’s volunteer work in cities would help solve urban problems, and their work was called "municipal housekeeping." Of course, the members of the Reading Class lived in a new suburban community, the antithesis of cities that many perceived as crowded and dangerous. Nevertheless, many Chevy Chase women left their suburban homes to volunteer in a variety of organizations. Clifford Howard's 1917 lecture on equal suffrage at the Chevy Chase Association is an excellent example of this concept of "municipal housekeeping." In this case, Mr. Howard claims that government administration is just a larger version of housekeeping, and thus women have the "experience and ability" to make a difference at the municipal and national level.

Creating a Sense of Community

As George Winchester Stone, Jr. wrote in one his memoirs of growing up in Martin’s Additions to Chevy Chase,

“A neighborhood is relatively easy to specify on a plat, but the sense of community therein resides in the quality of life given by its inhabitants.”

His mother Mary Bradford Stone was a member of the Reading Class from 1912 to 1915, and like so many other Reading Class participants, she was also a member of other groups, including the Chevy Chase Round Table, a Florence Crittenton “circle” in Chevy Chase which raised funds for the Crittenton Mission in DC, the Red Cross, the Women's Christian Temperance Union., the Y.M.C.A., the Women’s Club of Chevy Chase, and the activities of her church.

These organizations and institutions, in both Chevy Chase and the District of Columbia, created strong social networks and a sense of community in Chevy Chase. And they were essential to "the quality of life of the inhabitants," to quote Mary Bradford Stone’s son.

Again, in ways that affected individuals as well as their communities, women's club and voluntary activities were “...both a profit and a pleasure.

Reading Class Members: Read biographical sketches of the founders and early members. Reading Class Book Lists: read transcriptions of “The Outline History of the Chevy Chase Reading Class” (1899-1925) and nine annual reading programs (1919-1931).